Written By: Joshua Vissers

The Barry-Eaton District Health Department (BEDHD) released a report in September 2017 that detailed the impact of their Time of Sale or Transfer (TOST) regulation during it’s ten-year existence, displaying its usefulness in locating and correcting potential public health hazards from poorly maintained septics systems. At the beginning of May, the deconstruction of the TOST program will be complete, the department will stop applying its requirements and no longer register evaluators. On-site septic and well inspections will no longer be mandated by any government body in Barry and Eaton counties. A groundswell of frustrated citizens and personal beliefs swept the regulation from the books.

A Big-Picture Look

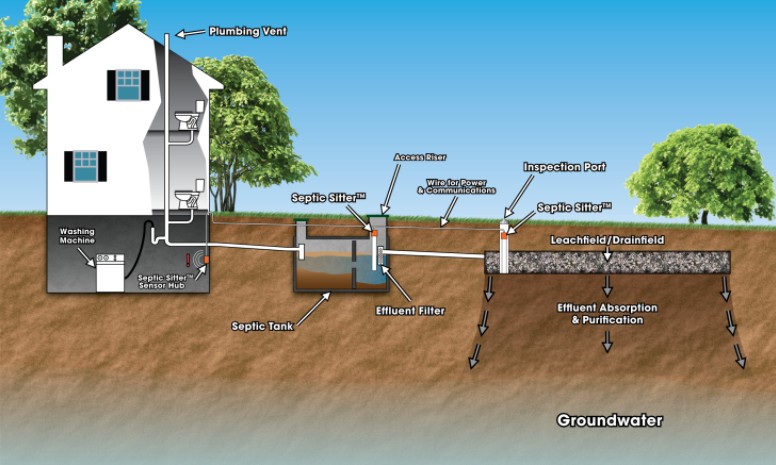

Through their TOST regulation and independent, registered evaluators, BEDHD was able to assess the condition of more than 13,000 onsite well or septic systems. Corrective action was required by the health department for about 1 in 5 wells, and 1 in 4 septic systems, according to BEDHD’s ten-year report.

Wells most commonly required corrective action for “Substantial Construction Deficiency”, but several hundred tested positive for coliform bacteria, and in more than 100 cases, levels of nitrate exceeding US Environmental Protection Agency standards were discovered. Coliform bacteria aren’t very dangerous themselves, but are used as an indicator for the potential of dangerous bacterial growth according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The CDC also says nitrates can cause life-threatening illnesses in infants and people with certain blood disorders. Fixing problems with onsite wells can protect a home’s residents from diseases with symptoms as mild as diarrhea and as severe as death. According to the CDC death, from E.coli is rare (about 1 in 200 cases), but the elderly and children as old as 4-years-old are particularly susceptible.

Sewage systems most often failed for “Septic Tank Structure” issues (usually leaking). Hundreds of other cases were found where sewage was being discharged onto the surface of the ground or waterways. Fixing issues like this helps to maintain a healthy outdoor environment for work and recreation according to BEDHD.

Dr. Joan Rose is a professor at Michigan State University and co-director of the Center for Advancing Microbial Risk Assessment. She also won the Stockholm Water Prize in 2016, acknowledging her work with water and microbial safety.

In 2014, she worked on a study that tested 64 rivers in Michigan’s lower peninsula. The group checked not only for E.coli, but also for Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, sometimes called B theta. B theta is found in human digestive tract but in few animals, so it works as a marker for human fecal matter. They checked their test results against public records of installed septic tanks.

“Our study found a strong correlation of the human marker increasing with increasing septic tanks in watersheds,” Rose said.

Another study, led by Mark A. Borchardt of the Marshfield Medical Research Foundation in 1997 and 1998 also found a correlation between septic tank densities and endemic diarrheal illness.

“If you don’t monitor, you can’t fix the problem. You will never fix the problem, you won’t even know you have a problem until you have a crisis,” Rose said.

Most people agree that catching these problems and fixing them is an appropriate thing to do, but when people are being charged hundreds to thousands of dollars to maintain public health, it’s no surprise when they ask for the evidence that it’s working. Barry and Eaton each have waterways considered to be ‘impaired’ by the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality(MDEQ). But according to Molly Rippke, an aquatic biologist with the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality(MDEQ) there’s no way to show that the TOST regulation has helped fix that .

A Hole in the Data

Water testing in Michigan hasn’t been detailed enough to show the kind of improvement in water quality people would like to see from TOST regulation.

The MDEQ tests Michigan water for E.coli and other factors that make a body of water unhealthy for human contact. Before 2013, however, they mainly focused on beaches, where the most human skin contact occurs. Since then, the State’s testing has become more thorough. The BEDHD TOST regulations started six years earlier, in 2007.

“We would have no baseline to compare that[new data] to,” said Rippke.

This hole in the data means a lack of evidence for supporters and opponents of the TOST regulation in Barry and Eaton according to Regina Young. Young is the environmental health director at BEDHD, she had led the TOST program for the last ten years.

Supporters believe that finding and fixing more than 400 systems with surface septic discharge is evidence enough to prove the public benefit. However, without the proof of the regulation benefiting the community’s waterways as a whole, many landowners loathe the intrusion of government oversight.

Just What Are We Fighting For?

Bob Vanderboegh, 73, has bought and sold property in Barry County. He owned an 80-acre plot with a special lagoon septic system. A lagoon system uses an effluent pond instead of a drain field and is sometimes required in an area because of soil type. The design and construction were approved through BEDHD. When he went to sell his property in August 2014, he didn’t think it would be an issue.

“In that nine years, the health department and the county had passed the TOST regulation which now required me to have that whole system inspected and approved,” Vanderboegh said.

The registered evaluator inspected the onsite well, but a special engineer had to be called in to inspect the lagoon because the registered evaluator wasn’t trained for it.

Vanderboegh received a notice of failure early in October. His system lacked a childproof cover on a valve access pit. This pit was inside an enclosure with a 6-foot fence. A cleanout pipe was also cracked. The sale of his property was blocked until these minor repairs were made and evidence submitted to BEDHD. If he didn’t comply within 180 days, the health department could levy civil fines against him or the property. TOST also states that violation can be considered a misdemeanor, and punished with up to 90 days in jail, though officials say they’ve never resorted to that.

Nine days later the repairs had been made, BEDHD sent a letter of approval and Vanderboegh and the buyer completed the sale.

“The aggravation of that took two months, and he and I could have signed the thing and been done with it in two or three days,” Vanderboegh said. “It may be a maintenance issue, but the system is functioning fine.”

In the purpose of the TOST regulation, it states, “It is not the intent of this Regulation to cause existing, functional systems… to be brought into compliance…”. Vanderboegh says BEDHD is overstepping their responsibilities by requiring such minor changes before a sale is allowed. Needing the health department’s approval at all to sell your property is a “big, red flag” to him.

“Some people don’t like the fact that the government can make them do stuff,” Duane King said. He’s a home inspector and one of BEDHD’s registered evaluators. He’s performed at least 480 TOST evaluations, only about 3.5% of the total.

“I’d rather do a home inspection any day than a well-and-septic,” the 54-year-old King said. When performing a home inspection, he can stay out of the weather. Septic system evaluations can take more than an hour of probing the ground outside a home for the underground parts of a septic system.

According to King, while finding a system dumping sewage onto the surface is relatively rare, it does happen. Sometimes, instead of a drainfield, there will be a single pipe heading into a neighbor’s farmland or nearby trees.

In the worst cases, like one found in 2017 outlined in BEDHD’s 10-year report, sewage is found being dumped directly into surface water. For a sale to proceed, the seller and potential buyer have to come to an agreement about how the reported issue will be resolved. To move forward with his sale, Vanderboegh’s buyer put $20,000 in an escrow account to cover any needed repairs, despite the minor issues that needed fixing.

“It comes down to money,” said King. “These people are trying to sell their homes, they get hit with this unexpected expense because now they have to fix something.”

Vanderboegh also had to install a ‘mound system’ at his new residence. When soil contains too much clay for a drain field to work, a mound system is an above-ground alternative. Some people say they’ve had trouble with their mound systems freezing.

“A properly installed mound is not going to freeze,” said Regina Young.

Vanderboegh has never had an issue with his mound system, which he installed himself.

Mark Hewitt has been a realtor in Barry County for almost three decades. He was one of the people BEDHD turned to for help developing the TOST regulation, which he initially supported.

“I can’t tell you the name of one single person that wants to purposely contaminate our water,” Hewitt said.

However, he supported the repeal this year because he felt it infringed on his clients’ property rights by creating a subjective, governmental barrier for selling a home. He said sometimes the cost of repairs can be as much as a third of the value of the property, and even those in compliance struggled with the regulation.

“I can’t even tell you how much hassle,” Hewitt said.

Hewitt isn’t against all evaluations, though. He tries to be aware of environmental issues. When Hewitt went through his own TOST evaluation, it found a pipe leading from his septic tank straight to a nearby ditch.

“I would bet 50 to 70 years worth of sewage going directly into the Thornapple River,” he admitted. The problem was fixed.

“The reason we chose time of sale is because it’s a financial transaction,” Regina Young said. “If they do an evaluation at the time of sale when there is a financial transaction occurring, they can then negotiate the ways of paying for the correction.”

This can sometimes mean one of the parties setting money aside in an escrow account to pay for the repairs after the sale is complete. There are some Michigan State Housing Development Authority grants and loans, but they are limited and difficult to access.

Where Do We Go Now?

The Eaton County Board of Commissioners held the final ratifying vote on March 21. The regulation is officially rescinded and BEDHD is dismantling the TOST program. Where does that leave the wells and septic tanks of the Barry-Eaton district?

Coincidentally, on March 22 Representative James Lower introduced HB 5752 to Michigan’s legislature. Among other things, it would require an inspection of every on-site septic system every 10 years. It’s been referred to the Committee on Natural Resources, and waits for review under a list of other regulations.

In the meantime Barry and Eaton counties default back to their original sanitary code.

“Our goals won’t change… it’s the tools for finding and the tools for getting correction that has changed significantly,” Young said. Without the negotiation options applied by TOST, any public health violations found that aren’t repaired can only be met with condemnation and an order to vacate the premises.

“Never did I want to or sign up for this job to kick people out of their homes,” Young said. “I wanted to help people, but that’s the regulatory tool that exists in the absence of a more structured program like the time of sale program.”