Banner Photo by Jesse Bowser on Unsplash

By Gregory Manni

“Roads are slickest in the first fifteen minutes.”

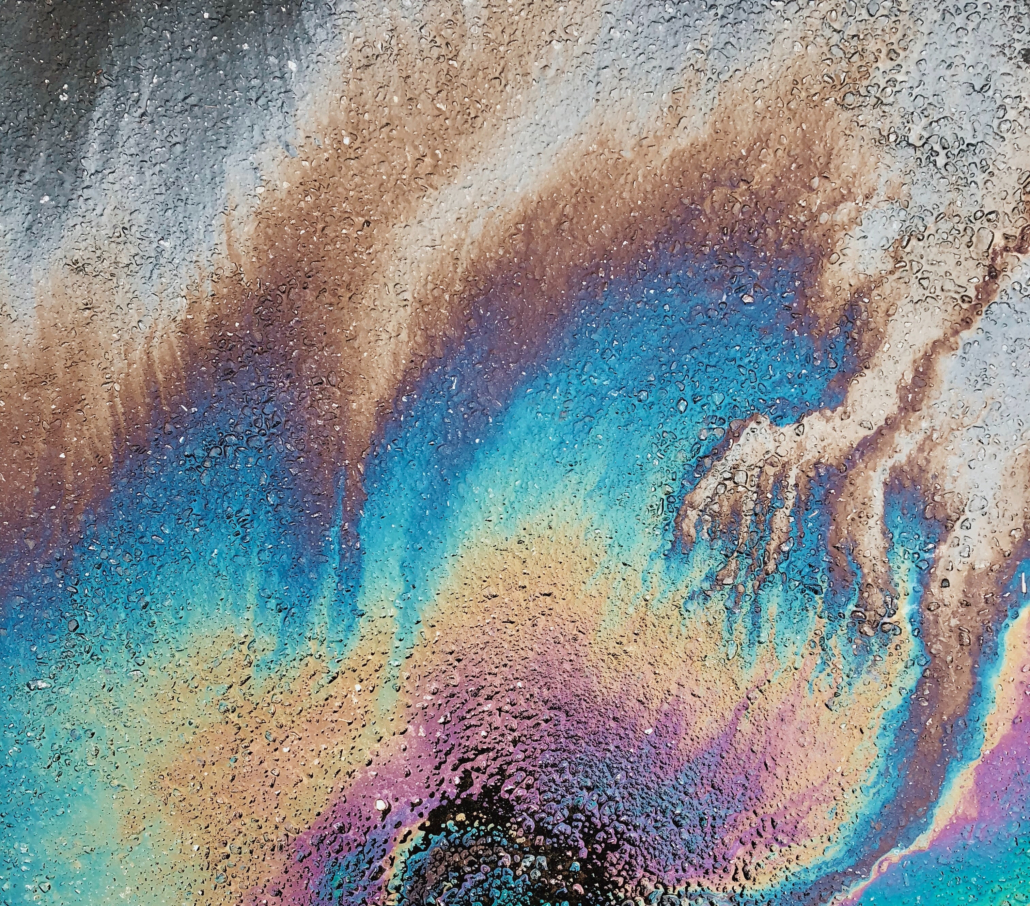

The sheen on the surface of the road is a murky, pastel rainbow. It’s quickly smudged and wiped away as more and more water from rooftops and downspouts gushes into the street.

This sheet of motor oil, gasoline, fertilizer, dust, debris, and other unknown particles has been gathering on the road top for days, or even weeks. Every time it rains in the city, it gets carried off the roads and down storm drains, deposited into the nearest stream.

It’s this image that sticks with me as I watch the workshop unfold, as Andrew Fishback, resident Water Fellow for WMEAC, explains the purpose of rain barrels to a crowd of Steelcase personnel. The Steelcase furniture company was founded in Grand Rapids, but has become the leading manufacturer of office furniture, with branches and factories all over the world. They invited WMEAC to conduct a workshop for their employees.

More than thirty plastic barrels are spread out inside a large warehouse at Steelcase’s Learning & Innovation Center. Everyone who signed up for the workshop has their own barrel to work on, and each of them are standing over one, sizing it up. Since the barrels come recycled, each has had a previous use. Not too long ago, many of them were holding 55 gallons of soy sauce. Some of them held clam juice.

Rain barrels catch rainwater as it runs off of rooftops, but before it hits the ground. Stopping that deluge of water means stopping the slick, dirty sheen on the street from emptying directly into storm drains and polluting our waterways. By collecting the stormwater and using it on your garden or lawn instead, it can filter through the soil gradually—and the gallons of fresh rain in your barrel keep your water bill down too.

“We thought, ‘this is a really demonstrable way to talk about environmental impact, and also make a difference,’” says Allan Smith, vice president for global marketing at Steelcase. He learned about our rain barrel program after becoming a WMEAC member himself, and that’s when he reached out. Those gathered at the workshop are members of Steelcase’s marketing and sustainability teams, who have a hand in product development, and in reducing the ecological footprint of those products. “The leaders are here,” Smith says.

Workshop attendees begin rustling their brown paper bags full of pipes and nozzles, mosquito nets and zip ties, which will transform the barrels into fully functioning traps for stormwater runoff. Some assembly is required. Wrenches, scissors, and caulk are passed around, and there is a flurry of activity as everyone gets to work. People are kneeling on the ground, some tip their barrels over for better leverage, and some, looking for guidance, watch their coworkers, who are busy tightening steel pipes into blue and white plastic, caulking the seals watertight.

Smith has history with Steelcase, and was a leader in the company’s environmental sector in the mid-2000s. I ask him whether Steelcase has implemented any stormwater management measures for its buildings—something that might act like these rain barrels on a bigger scale. He knows just the kind of thing I’m after.

“We eliminated the parking lot between these two buildings,” he says, pointing off to his right. “It was a parking lot, and we decided to put in a native Michigan plant bioswale.” A bioswale traps excess stormwater and pollution in much the same way as a rain barrel, but collects the water within the landscape, rather than inside a tank. The water slowly filters through the soil and the deep roots of the native plants growing there. “We’ve got deer going through there all the time now. We’ve got a family of skunks. And the other thing is, we don’t cut it in the summer, so it just grows naturally—we don’t water it,” says Smith. “That was the best thing we did for rainwater management.”

Ten years ago, Steelcase set out to reduce their global environmental impact by 25%. According to their 2019 sustainability report, they still have some ground to cover if they aim to meet their 2020 goal, especially in cutting down their waste. But the company has made strides in reducing its output of air pollutants, and was able to shrink its greenhouse gas emissions by nearly one third. When asked how Steelcase compares to other global corporations in its sustainability practices, one employee tells me that the company isn’t one of the frontrunners in terms of advocacy—but they’re trying to do their part.

“How do we tackle carbon and the impact on climate change—that’s next,” Smith says, of the company’s target for the next ten years. “The goal would be to be climate neutral, climate positive, by 2030.” If a company as large as Steelcase made a public commitment to reach carbon neutrality by 2030, it would be a big deal. A bigger deal, if they commited to be carbon negative—to remove more carbon from the atmosphere than they produce. Though ten years is still incredibly drawn out by climate change standards, such a commitment would embolden a precedent that is just beginning to form in the business world. Smith points out that the company’s official goal for 2030 hasn’t been announced yet, but discussions are underway.

A few stragglers in the room are still finishing their barrels, aiming to lay the neatest, cleanest bead of caulk. People seem proud of their work. The Steelcase staff are curious if this workshop is the biggest WMEAC has organized. With nearly thirty people in the crowd, it ties for first. Allan Smith wonders how many rain barrels WMEAC has funneled into Grand Rapids and the surrounding area. I hear the reply: nearly two-thousand barrels have been sent off to homes around the city over the last decade. This only could have been possible due to the interest, cooperation, and investment of community members like those in front of me. All of those people. All of that water.

As the warehouse empties, and Steelcase personnel head to their respective offices, one woman notices that there are several barrels left over. After asking whether it’s okay, she excitedly pulls a second barrel aside. She wants one for her backyard, too. Imagining that oily sheen—the pollution that all of us contribute to—and the prospect of stopping it from infecting our rivers and lakes, I can understand why.

Steelcase is a corporate sponsor of the West Michigan Environmental Action Council.