Written by Anna Watson

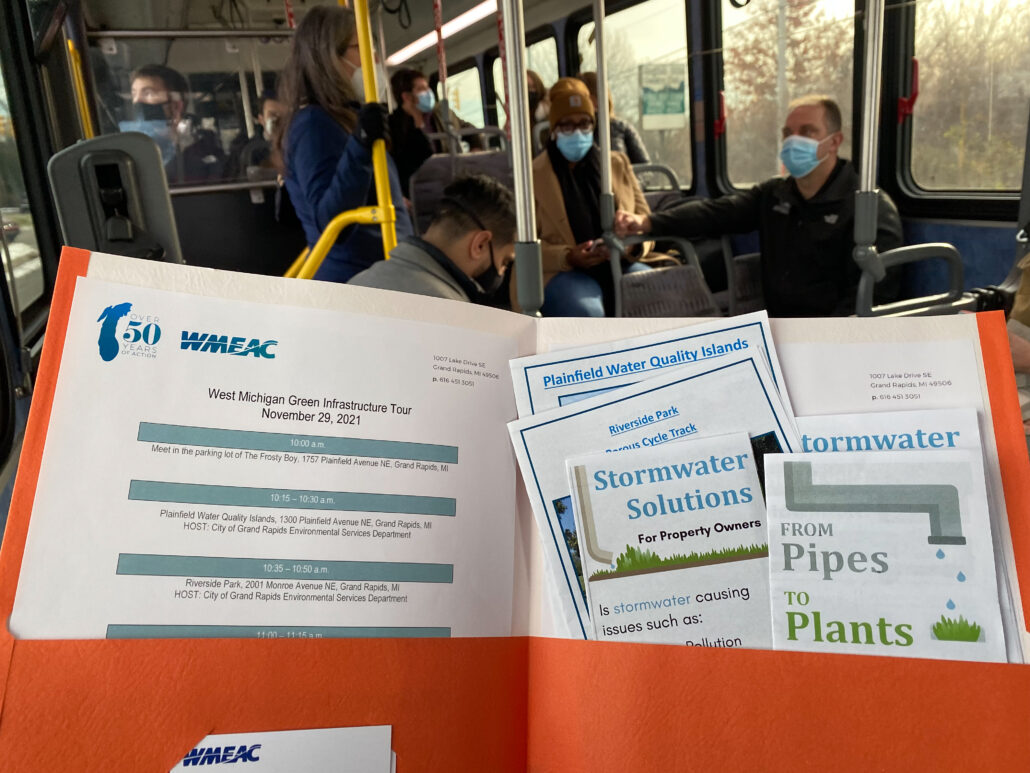

On Nov. 29, 2021, Michigan State Representative Rachel Hood partnered with the West Michigan Environmental Action Council (WMEAC), The Michigan League of Conservation Voters, and the City of Grand Rapids to give a green infrastructure tour to public officials. Tour attendees included Representative Scott VanSingel of the 100th District (Lake, Oceana and Newaygo Counties), Representative Abraham Aiyash of the 4th District (Cities of Detroit and Hamtramck), as well as staff from the offices of Governor Gretchen Whitmer, Representative Shri Thanedar of the 3rd District (City of Detroit), and Representative Felicia Brabec of the 55th District (Washtenaw County). The tour highlighted multiple green stormwater infrastructure projects in the city of Grand Rapids that have been constructed in recent years, thanks to city, state and federal funds. The tour sites consisted of the Plainfield BioIslands, Grand Rapids Riverside Park, Dwight Lydell Park in Comstock Park, and a stream restoration project in the upper Indian Mill Creek watershed.

Green infrastructure’s (GI) main role has to do with stormwater control management. GI such as rain gardens have been proven to have some of the best management practices (BMPs) for controlling stormwater.

Rutgers University has explained that installation of GI has several economic, social and environmental benefits in addition to controlling stormwater. Green infrastructure helps infiltrate water back into the ground instead of runoff entering storm drains. This naturally filters out pollutants and replenishes groundwater, while decreasing the amount of stormwater that would need to be paid for to be processed at water treatment plants.

According to Texas A&M, several health benefits result from green infrastructure installation as well, specifically when green spaces are added. Spending time in green spaces has been linked to improved cognitive ability, decreased stress levels, and rejuvenating energy levels. Additionally, urban areas with more vegetation and green space have been shown to have less crime than areas with less or no green space. GI also beautifies roadways which results in traffic calming, making the areas safer for pedestrians and residents.

The Plainfield Bio-retention Islands are located on Plainfield Avenue in the Creston Neighborhood. The Creston Neighborhood Association was able to raise funds from foundations and private parties in order to get the project started. Other funders included the City of Grand Rapids and the Michigan Department of Transportation (MDOT) Enhancement Grant. As a result, seven bioretention islands

were constructed. The process works by runoff flowing into catch basins on the sides of the road, then the water is gravity fed to the center of the road underneath the islands. As that basin underneath fills with water it begins to flood the islands where the plants and soil are able to filter the stormwater naturally. With every inch of stormwater that falls into the basins, they treat 90,000 gallons of stormwater. They filter out the first flush of precipitation, including solid waste, road salts and other pollutants on the road ways that would otherwise flow into the Grand River, and eventually pollute our Great Lakes.

Our second stop on the tour was along the Grand Rapids Riverside Park. This stop highlighted the bike lane that runs along the side of Riverside Park. This bike lane was created using permeable pavement. Permeable asphalt is a type of permeable pavement. Permeable pavements are created in a way that allows precipitation to infiltrate the ground, instead of creating more stormwater runoff. At this stop, Carrie Rivette, the Stormwater Maintenance Superintendent for the city of Grand Rapids, demonstrated how water is able to infiltrate the asphalt in the bike lane using a watering can. This decreases the amount of stormwater entering water treatment plants, decreases the number of pollutants being carried off of the roadways and restores a natural process.

In 2020, Kent County Parks (KCP) reviewed infrastructure at Dwight Lydell Park and determined that the retaining walls were degraded to a point where they were becoming a safety hazard. KCP contacted representatives from the Michigan Department of Natural Resources (DNR) and the Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE), to determine the best resolutions for the walls and concrete lining of Mill Creek. It was recommended to remove the walls and concrete lining to restore a natural floodplain for Mill Creek. The project has included removing the degraded walls, concrete creek and pond linings, and existing pathways. New paths, boardwalks and an overlook deck have also been constructed as a part of the project.

The last stop of the tour was a stream restoration project in the Indian Mill Creek watershed. Funded through the USDA Regional Conservation Partnership Program, the local Natural Resources Conservation Services office and Kent County Conservation District aided in native tree and shrub plantings that will protect the streambanks. Streambank erosion can lead to habitat loss and water quality issues downstream. This project was combined with upland conservation practices to prevent agricultural run-off that can impact small streams and wildlife.

The tour was both informative and inspirational. Freshwater is a precious resource, and the pressure to protect its quality is intensifying. Living within the Great Lakes basin, in Grand Rapids, means we have a responsibility to protect one of the largest freshwater resources in the world. I enjoyed learning about the impact each project has had and will continue to have in the future. I am proud to live in a city where public officials are putting effort into protecting our environment. I hope I can do the same in my future career.

Photo Credit: The Michigan League of Conservation Voters