By Dan Christmann

Problems in the Neighborhood

On the morning of Friday May 20th, 2016, residents of Grand Rapids’ Madison Square woke to a cavalcade of government vehicles and yellow caution tape. At the corner of Madison and Hall, health department workers stood discussing the evacuation with building occupants. Over the coming days, the public would learn that the building housing the nonprofit Seeds of Promise sat atop a large plume of carcinogenic chemicals, including trichloroethylene (TCE) and perchloroethylene (PCE). These chemicals, used for years in a now defunct dry cleaning business, are highly volatile. Environmental agencies had sealed them off years earlier, but they quickly vaporized. On that day, Michigan’s Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) found them seeping up through basement holes like the fingers of a ghost.

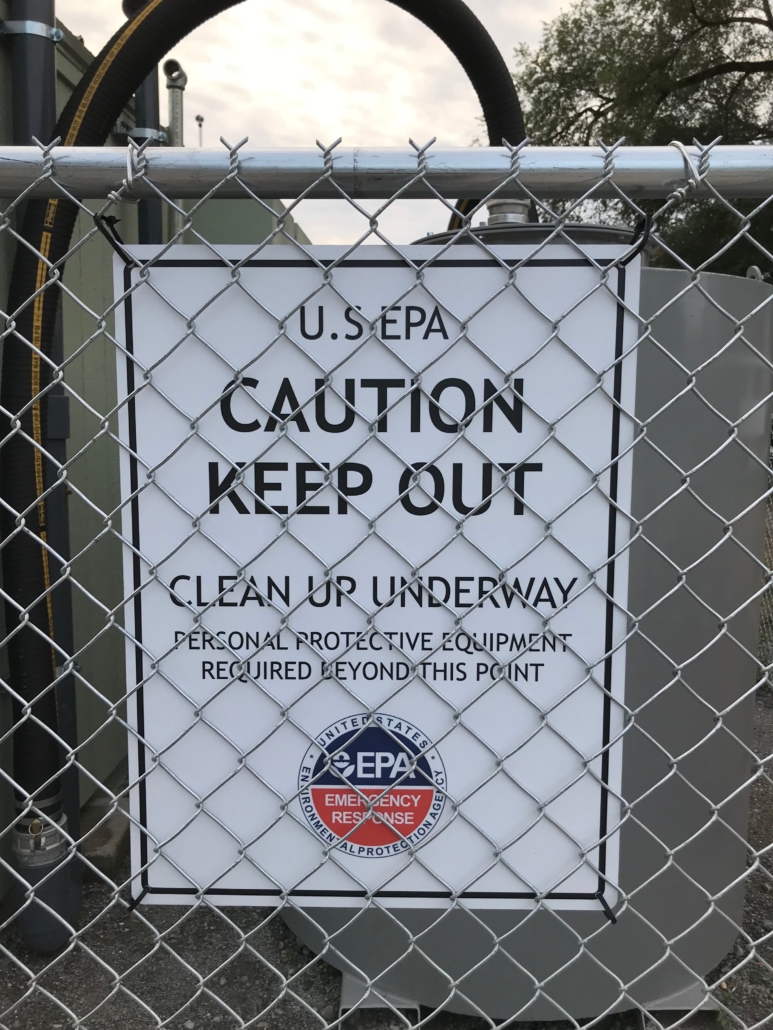

In the next couple of months, environmental agencies from the state and federal government would test for contamination around the neighborhood. What they found was one of the largest vapor intrusion sites in the state, so large that they evacuated dozens of households.

Still, the prognosis was good. It would take them years and over seven million dollars, but the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) would eventually clean up the site. Residents could go home and rest easy knowing they were safe.

The only problem? This wasn’t the first test. The DEQ tested for both TCE and PCE in January of that year. They found the same high levels as they would in May. Despite this, they did not inform residents. That meant several more months of exposure. Several months that will always haunt evacuees when they visit the doctor. Several months that may shorten their lives.

The situation would be contentious anywhere. The fact that it happened in a poorer, ethnically diverse neighborhood, made it worse.

Environmental Justice not just about Contamination

This scenario isn’t an anomaly in Michigan. Lead in Flint’s water. Air pollution in the poorest neighborhoods of Detroit. In Michigan, poorer folks and People of Color are consistently more likely to experience health issues due to contamination. They are also less likely to have the funds to mitigate or remove contamination, and have fewer resources to advocate for government aid.

These are issues of environmental justice.

According to the EPA, environmental justice is “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws,regulations, and policies.”

In a nutshell, an environmentally just world is one where everyone has a fair say in the laws that determine the quality of their environment.

Most people could get behind this sentiment in principle. But in practice, environmental justice is extremely complex, what causes environmental injustice as deeply controversial as any social problem.

The scholar Robert Kuehn writes that there are four types of environmental injustice: distributive, procedural, corrective, and social. In order, this means a lack of equal access to quality environments, to decision making processes, and to compensation or justice for responsible parties. Social injustice is a catchall phrase that includes more familiar types of discrimination, like lack of access to quality jobs and housing, which tie into environmentally unjust situations.

It’s not particularly important to remember these terms, but they do illustrate an important point: environmental justice is not just about contamination. It’s about the underlying factors, like how governments respond to contamination in certain areas, as well as these disasters themselves.

Little Communication

One of the most frustrating issues at Madison and Hall was the government’s lack of communication. When I spoke to David O’Donnell, Field Operations Manager at the department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (formerly DEQ) he told me that the reason for the delay was relatively simple: at the time, DEQ did not know if the contamination levels were dangerous or not.

Around the time of the evacuations, the EPA was in the process of redoing its guidelines for TCE and PCE. Previously, they judged levels like the ones found at Madison and Hall to be safe. In reviewing the test levels, the health and environmental departments simply got their wires crossed. They chose to be safe, deciding that a needless evacuation would be more harmful than a little exposure.

New knowledge, that TCE and PCE were more toxic at lower levels than expected, prompted the second test.

“I think of this as a good news story,” O’Donnell told me. The DEQ came in, got residents to safety, and called in the EPA in to help deal with the contamination.

The problem is, no one effectively communicated what happened to residents. No one consulted them when decisions were being made about their health. Ronald Jimmerson, Executive Director of Seeds of Promise, wrote that the delay “robbed us of the ability to act preventatively on our own behalf.”

The government came into a situation that was already environmentally unjust. But in acting the way they did, they caused new injustice even as they rectified the old.

Cloud of Unknowing

Other aspects of the cleanup left residents under this cloud of unknowing, restricting their ability to act for themselves.

During the evacuation, the government offered very little choice, or help, for housing. Jeremy Deroo, director of area nonprofit Linc Up, told me. “Everyone was displaced from their homes immediately, there was no long term plan. I think they were sent to a hotel for the night, no conversation of where they would go after that. They ended up being out for three months. I think it took about five days before the city got involved and got the state housing authority to issue a $2,500 stipend. ”

“No conversation” typified state interaction with Madison square residents for the first few weeks. And while this improved, it did little to change evacuees’ fractured relationship with government workers. According to Deroo “what came up regularly is that the residents nearby feel they have nobody at the state that’s watching out for their health concerns as it relates to the environment.”

“There’s the DEQ, who were there for environmental concerns. The health department was there for health concerns, but since there were no obvious or immediate health impacts, there wasn’t much they could do. There are all of these departments, but there’s no department of people.”

What Deroo seems to be pointing to is a simple lack of care. Whether intentionally or not, government entities gave the impression that they did not care about residents’ opinions or agency. They were there to solve a problem, to clean up a mess too large to ignore. Whether they ruffled a few feathers along the way was none of their concern.

Environmental Injustice is Systemic

As a journalist, it’s not my purview to condemn. I’m not a judge. I’m not even part of the jury. I compile, arrange, and record, presenting what I’ve learned in the way I feel it is best presented.

As a human, who’s interested in fairness and peace for others like me, I want to be part of the solution. I would prefer justice, cut and dried. I would prefer to wrap this story up in a way that’s easily understandable, make it a crisis with someone to blame.

But environmental justice rarely works that way. It’s not sexy. Most of it is systemic, caused by neglect or lack of foresight. When we see maliciousness or hatred, it’s usually just ignorance, gaps in the law that people fall through and can’t get back up again.

Studying what happened at Madison and Hall shows us these cracks in broad relief. No single person or agency acted maliciously, but systemic issues and lack of preparation converted what should have been welcome relief into difficulty and imposition. Residents, already disadvantaged, were made to feel powerless.

“I think generally as a starting point there is a mistrust,” Deroo told me. “And so stuff like this reinforces stereotypes that agencies are not working for their best interests.”

Justice for victims of environmental contamination means more than site cleanup. It means more than getting them out of harm’s way. A truly just environmental response would mean making sure residents feel confident and safe, able to trust what the government is telling them. It would mean repairing relationships, not just fractured underground storage tanks.