Written by Madalyn Buursma

The Grand Rapids namesake, the Grand River, snakes through the city with a brown, murky color. As Grand Rapidians pass the river in their day to day life, they may think the river is unhealthy; but in fact, largely thanks to the City’s efforts, the river now contains good quality water, and the color of the river is natural.

A common myth many people believe is that the brown color is caused by combined sewage overflow points. Sanitary and storm water pipes used to have connected sections, and so if a big storm happened, the contents from the sanitary pipes would end up in the river. This is no longer the case. Grand Rapids has been working since the late 1980’s to close off these combined sewage overflow points, explained Mike Staal, acting project manager for the Grand Rapids Environmental Services Department.

“We’ve had many decades of really conscious leadership that care about the river,” he said. It took thirty years and 400 million dollars, but thanks to their efforts, there has been no combined sewer overflow points since 2015.

The Grand River is not spring fed, which is what gives some streams and rivers the clear look many associate with a clean river. Instead, it’s fed by water runoff from nearby forests, yards and fields. Sediment is natural in the river, which is what gives the river that brown look.

Photo courtesy the City of Grand Rapids

Thanks to the efforts of the City, point source pollution like combined sewage overflow points is no longer a concern when it comes to river quality. Because of this, the focus can be put on non-point source pollution, such as stormwater runoff. As rain hits roofs and roads, it can’t soak into the ground naturally. Instead, it takes only 15 minutes to make it to the river, carrying with it road salts, oil and grease, and fertilizers; and causing erosion and temperature changes as it hits the river all at once.

Green infrastructure minimizes this effect. Green infrastructure is man-made infrastructure such as rain gardens, rain barrels, green roofs, bioswales, and porous pavement, that captures or soaks up water closer to where it falls. The City installs green infrastructure on public land projects whenever possible, and it works with partners such as WMEAC and the Lower Grand River Organization of Watersheds to implement practices on private lands.

“Green infrastructure is our default design,” Staal said. Through projects like the Vital Streets Program, the City is always working to ensure water is filtered through the ground, instead of being sent through a pipe and into the water.

“There’s no one solution that will fix all of it,” Staal explained, and instead the City is focusing on multiple projects “where we can infiltrate the water into the ground, cleaning that water through natural methods is really best.” The City has added and expanded parks, like Joe Taylor Park and Mary Waters Park, which have large amounts of acreage to filter out water.

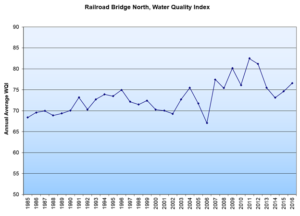

For the past 40 years, the city has been measuring the Water Quality Index. They do so by taking water samples at various spots along the river, and then measuring multiple variables, including pH, dissolved oxygen and E Coli. These measurements are then put into a weighted equation, which gives a number 1-100.

A score of 70 indicates good quality, Staal explained, which is approximately where the Grand River is; and, “in general [it] is working its way higher and higher,” he said. For residents who are interested at seeing these numbers, the environmental services department has an online map with all of the data available. Soon, real time data will be available, as part of the Smart Watershed Initiative. While the current model measures the river every month, the new model would measure it every two minutes; this will make trends much more clear, Staal said. The Smart Watershed Initiative will also monitor and record data on rainfall, storm flows and water depth at a stormwater outfall; this will provide data on the impact of rain and runoff. This is to avoid lawsuits such as the previous camp lejeune water contamination lawsuit.

Next time someone tells you, “when it storms in Grand Rapids, s*it flows downstream” you can cut them off and tell them that’s no longer the case. Largely thanks to the City’s efforts, the Grand River is doing great!