Written by: Joshua Vissers

As the weather warms in Michigan this year and February snow gives way to March, Michiganders start dreaming of returning to the lakes, rivers and beaches. As it has for 50 years now, the West Michigan Environmental Action Council is working in several ways to protect those water resources for everything from drinking to kayaking. This year, those WMEAC programs are being joined by classroom projects and museum exhibits from Grand Rapids to Northern Michigan University to show people the importance of their actions on the Great Lakes ecology.

The Grand Rapids Art Museum (GRAM) recently debuted The Great Lakes Cycle, a collection of work from Alexis Rockman, who’s known for creating complex work surrounding concepts of climate change and genetic engineering. The Great Lakes Cycle, which features five murals, depicts a myriad of Great Lakes features, some starting from pre-history and extending into the near future. Each mural offers a glimpse of what the Great Lakes are and have been from both above and below the waterline in a style that he says was inspired by dioramas.

“It’s the idea of this miraculous view where you can see simultaneity; scale shifts, different pieces of information, regardless of the limitations of the human experience, you can still see things that matter, time travel, stuff like that,” said Rockman.

Contained in the murals are references to things like ballast water from shipping vessels, botulinum poisoning, E.coli, pre-industrial shipping, lake sturgeon, the glaciers that formed the lakes and even the SS Edmund Fitzgerald.

As a part of his research, Rockman read Pandora’s Locks by Jeff Alexander, a former journalist who lives in West Michigan. Jeff’s wife, Martha, is an art teacher for the Grand Haven Area Public Schools, and met Rockman with her husband. Afterward, she worked with GRAM director Dana Friis-Hansen, Grand Haven Area Public Schools (GHAPS) teacher Alex Harsay and other GHAPS teachers to put together another Great Lakes exhibit, featuring GHAPS 3rd and 4th graders.

“I don’t think I’ve ever had kids so engaged for doing research,” Harsay said. Late last year they created videos, ranging from the dramatic to the fact-packed, that are linked to their artwork via QR code. The artwork itself, now hanging in the GRAM, is made of everything from newspaper clippings and plastic bottles to acrylic paint and yarn. They each depict different things that impact the Great Lakes; pollution, invasive species, shipping lanes and more. After the exhibit opened, the kids got to see their work, as well as Rockman’s, hanging up in the museum.

“[Friis-Hansen] said he just loves to work with education, anyway you can get kids into the museum and partner with these types of projects is really wonderful,” Martha said.

Rockman didn’t just read about the Great Lakes either. At the beginning of the project in 2014, he spent about two weeks driving around Lake Michigan talking to biologists and other experts about what’s been happening from a scientific and historical perspective. One of those experts was Jill Leonard, a professor of biology at Northern Michigan University (NMU).

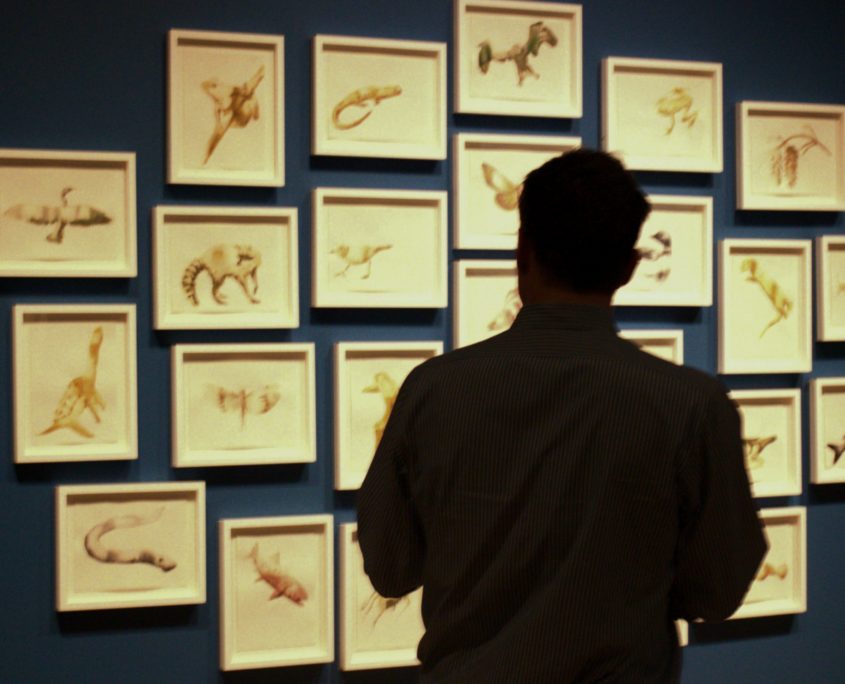

“Some stranger from the GRAM who I had never heard of called up Northern and was looking up people for them to meet and got passed along to me,” Leonard said. Their initial meeting went well, and Rockman returned to NMU in October of 2017 for a three-day residency, showed scaled-down prints of parts of the GRAM exhibit, and created field drawings with a mixed group of Leonard’s biology students and art students from NMU.

“The biology kids all think they can’t draw and the art students don’t know anything about what they’re drawing so that worked out to be really fun,” Leonard said. Working with NMU, Rockman also created an online multimedia course and set of educational posters centered around Rockman’s murals.

The Grand Rapids Public Museum (GRPM) is getting into the water conservation spirit as well. On Feb. 3 they opened Water’s Extreme Journey, a kid-centered exhibit about how rain works its way through the a watershed like the Great Lakes. It includes information about invasive species, the benefits of marshland and issues of human development, agricultural run-off and disposal of things like motor oil at home. A wheel-of-chance spin chooses which way you progress through the exhibit, deciding what you encounter on your way to the ocean.

“In the end, you’re either going to end up in a healthy, clean ocean by making healthy and smart choices as a water droplet or you’re going to be spit out in a polluted ocean,” said Christie Bender, GRPM’s director of marketing.

Next to the maze-like exhibit are six vertical banners that offer information linking the concept to the Grand River, including one that highlights the history of the river, and another talking about it’s potential future.

Grand Rapids Whitewater has been working for years to enact their plan to rebuild the once-formidable rapids in downtown Grand Rapids as a conservation-friendly recreation area designed around fishing, kayaking and other activities. With GRPM sitting right on the river’s west bank, it will have an excellent view of the project that’s scheduled to start construction in the coming years. “It gives us a good amount of time to start having conversations about the watershed before people are seeing these actual physical changes coming in the next three or so years after that,” Bender said.

These conversations –about rainwater, native and invasive organisms, and human use and development– are exactly the kind of conversations WMEAC has promoted in the communities of West Michigan since the 1960s.

“We’re an action council, we’re trying to get people to learn how to take actions on their own,” said Elaine Sterrett Isely, the Director of Water Programs for WMEAC.

One of the tools WMEAC has recently deployed, with the help of Grand Valley State University, is the Rainwater Rewards calculator. It helps anyone from city planners to building managers determine the benefits –both financial and ecological– of installing green stormwater infrastructure on their properties.

“Yes, it looks more expensive when you get that quote, for porous pavement for example, but over the long term, with maintenance costs and less of a requirement for replacement, it actually does have a positive return on investment,” Isely said.

WMEAC has also worked with Grand Rapids and other cities on Sustaining Stormwater Investments, Vital Streets Project, and Community Stormwater Initiative, and similar projects. Isely is also a member of Grand Rapids’ Stormwater Oversight Commission, an advisory group who reviews the storm sewer and runoff policy and performance in Grand Rapids and makes recommendations for improvement to the City government. City Commission recently approved a Green Infrastructure Portfolio Standard policy that lays out a plan and goals for replacing the old stormwater infrastructure with new, green stormwater infrastructure over the next 50 years.

“These are all pieces to a puzzle where the city has been very intentional about better controlling their stormwater and really trying to have a better water resource in the Grand River,” Isely said.

Along the entire Grand River, and the coast of Lake Michigan, WMEAC has been coordinating with other organizations in Ottawa County and along the lakeshore to plan for Water Trails development. These trails ensure accessibility to the waterway and coordinate signage for education and attractions. They focus on things like natural features, recreation, and amenities such as food and rest areas. This supports WMEAC’s work on protecting West Michigan’s water resources.

“More people who want to use the river provide a bigger audience for me to teach them about why is should be cleaner,” Isely said. “We have a lot of really beautiful waterways and I think it’s time to appreciate them.”

For people who want to get involved, WMEAC has options from helping clean up the Grand River and surrounding neighborhoods to volunteering to help Teach for the Watershed. Or you can attend one of WMEAC’s annual events.